CHAPTER 17: CHUCK BUCK BECOMES PRESIDENT

June 1979! Marked another of those historic milestones in the long march of Buck Knives to its present status. It was then that Alfred Charles Buck, the 69-year-old chairman and president, turned over the presidency to his son, Charles Theodore Buck, then 43 years old.

The term "bittersweet" may have been coined to describe just such an occasion. Al Buck was enormously popular, and his friends were delighted that Al and Ida would now have time to enjoy the fruits of their labors. At the same time, those friends who were stockholders may well have had some reservations. Sales were on their way to another record high in 1979. The value of Buck stock, which sold initially for $10 a share (without a noticeable lineup of prospects for shares, at that), had soared out of sight by now.

"I had some big shoes to fill," Chuck Buck noted. "Dad had done an incredible job. It occurred to me that it would be hard to come up with an encore. But like his father, and his father's father, Chuck Buck was a man of faith. He believed in God, and he believed in Buck Knives. And such faith was obviously well-founded.

Throughout the company, the new president was known simply as "Chuck," and the informality of the greeting matched the man perfectly. Warm, personable and approachable, Chuck's easy-going manner was more buddy than boss.

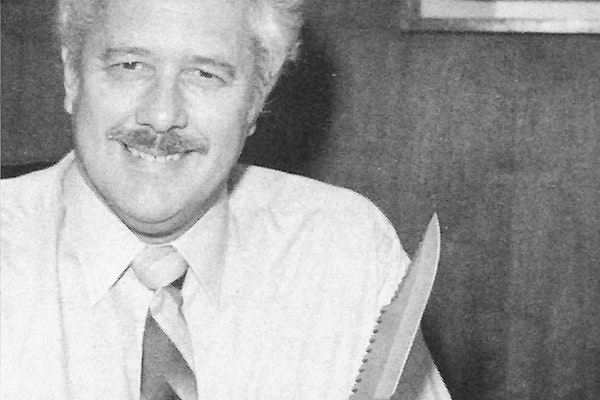

Actually, Chuck Buck already had begun putting his own personal stamp on the company. Seeing the need to improve employee relations, he had initiated a variety of programs designed to knit the various elements of the firm together. Foremost among them was the production incentive program that went into effect in 1978.

In short, the program worked liked this: Buck managers would establish specific production quotas which, if met on a weekly basis, would enable the company to achieve its annual goals.

The company then offered tangible incentives to surpass those quotas. When they were exceeded, Buck promised, the additional revenue would be divided equally between the corporation and the employees themselves. For many Buck employees, such bonuses increased their take-home pay by as much as 25%.

"The employees were skeptical at first, but when they started seeing production bonuses in their paychecks they warmed to the idea real quick," Buck said. "I'm not even sure who came up with it, but it was a great idea. It gave our employees a way to increase their salaries. The profit-sharing element helped re-unify the company.

And knowing that we would meet our production quotas gave our sales people great leverage in the field. "Chuck Buck's aggressive commitment to growth was another of his bold steps forward as the new president. He was convinced that, for 18 years, the company had grown reactively, responding to increased demand. Buck felt the firm should expand proactively, to pursue and seize greater demand.

"In the late '70s, I remember reading a story saying that sales in the sports knife market had reached something like $400 million a year in retail sales," he explained.

"I was shocked at how big the market apparently was, and I didn't think we were commanding a big enough share. I began to believe there was a major market out there, bigger than we'd ever realized. And," he concluded, "if we didn't go after it, somebody else would."

Most of the world's larger knife manufacturers are privately held. As a result, accurate sales figures are hard to obtain. Still, informal inquiries seemed to confirm a basic fact: While it was true that Buck's sales were growing steadily, the firm's share had remained relatively flat for five years. Chuck Buck was determined to spur real growth, and this commitment triggered a series of decisions that shook the company right down to its heels.

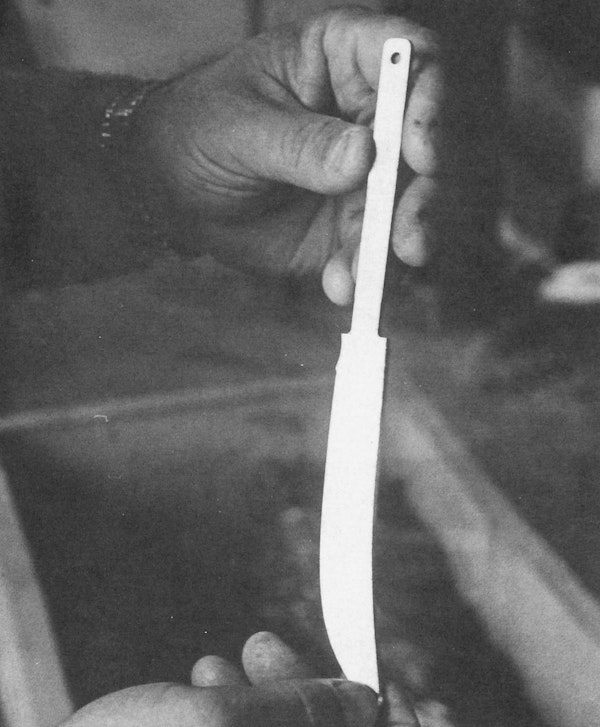

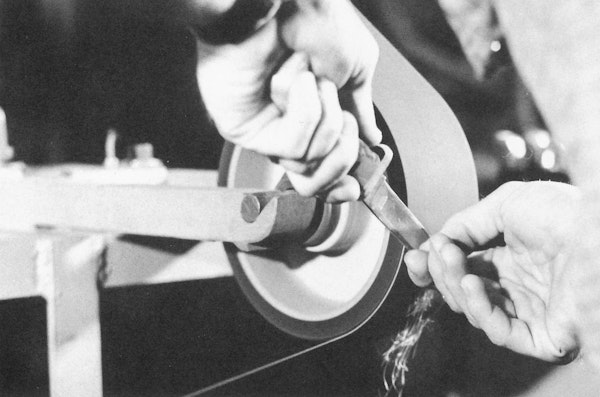

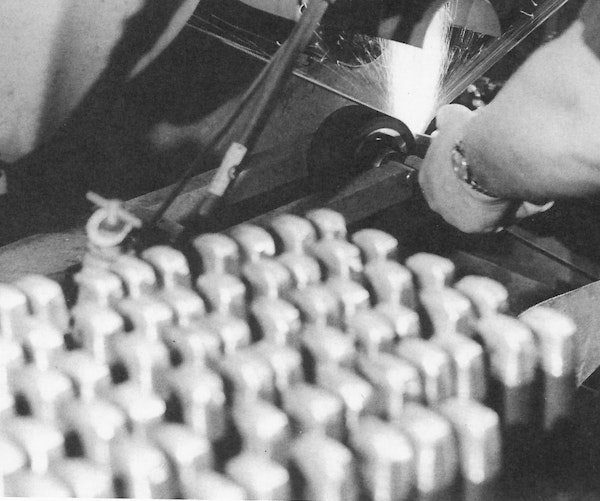

Essentially, Buck felt this commitment would require modern ideas, modern systems and modern young men to craft them. "In many ways, we were still doing business the way we had done it on Congress Street the day the corporation began," Buck explained. "Those systems were fine when we were making 100 knives a week, but when we began making 100 knives an hour we began overloading our systems. And by 1979, we had gone about as far as we could go with the systems we had in place."

In one area of the company, Buck felt the needed transition had already begun. Everett Gile, who was hired in 1977 to replace Craig as vice president in charge of manufacturing and engineering, had earned high marks for his professionalism. Buck had confidence in the sales network being administered by Ham; at the same time, he felt the company needed to expand its abilities in two critical areas: finance and marketing.

Specifically, he felt that shortcomings in these areas were jeopardizing one of the company's oldest strengths, its responsiveness to dealers. For 20 years, Buck Knives had processed and filled orders far more efficiently than any of its competitors. By 1978, with the new and larger computer system not yet in place, the backlog of orders grew almost daily. Ironically, many were placed in cardboard boxes in the hallway outside the accounting office. There they remained until they could be processed.

In 1980, Buck made a key move by naming Gary Schwertly the company's chief financial officer. Schwertly had been CFO at Carbo-Medics, Inc., and division controller for Reed Irrigation Systems. Of special value to Buck, he was well versed in computer tech-nology, and had considerable experience in using computer software to streamline corporate accounting. Schwertly, now senior vice president of finance, was surprised to discover how unsophisticated the company's business procedures had been.

"The financial operation here was not automated at all," he said. "When I arrived, we were still using a manual general ledger system. There was no cost accounting. We couldn't establish margins on any of our lines. "For my first couple of months on the job, I carried a notepad around and made lists of everything that needed to be done. Fortunate-ly, Chuck was very receptive to new ideas. When I told him what I wanted to do, and why I thought it was important, he was usually very supportive."

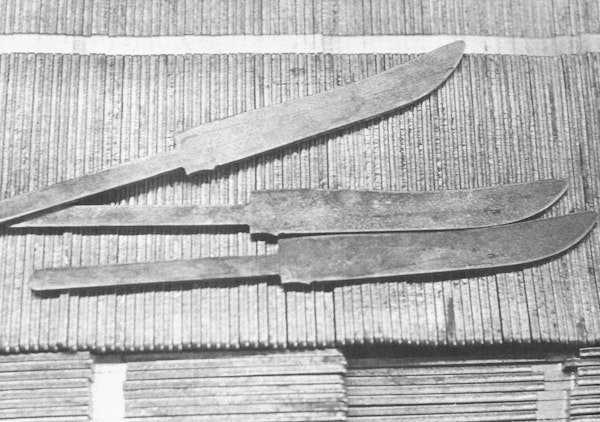

Some months after he arrived, Schwertly, with full support of cost accounting manager Jim Miller, carefully structured a cost accounting system for each model in the Buck catalog.

To his horror, he discovered that several were actually costing more to produce than the company realized in sales.

"At the time, we made a three-piece set of kitchen knives called the 'Empress Trio," Schwertly recalled. "When we finally got all the costs put together, we learned that every time we sold one, we actually lost four or five dollars. We stopped making the Empress Trio."

In addition to streamlining procedural matters, Schwertly altered some of the company's fiscal policies. For example, until 1980, the general checking account regularly carried a balance exceeding $1 million. He moved unneeded reserves into investments that produced substantial returns. In hopes of broadening the company's horizons, Buck named Jim Bloom as its Director of Marketing in 1981. Bloom had been the Rocky Mountain sales manager for Wilson Sporting Goods Company. While Wilson didn't sell knives, Bloom knew many of the retailers being served by Buck. More importantly, he brought a national perspective to a company now anxious to expand its reach.

Such business refinements, combined with continued strong sales, helped Buck rack up another record year in 1981, and net income returned to a level it had not equaled since 1978.

As he gazed toward the Southern California foothills that can be seen from the executive offices, the president of Buck Knives may well have had mixed emotions.

True, the transition was working. The annual report was evidence of that. But Chuck Buck, a sensitive man who cared for those moving around him, did have mixed emotions.

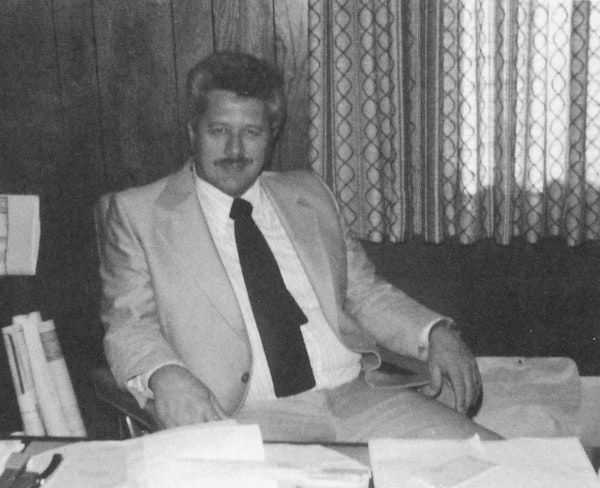

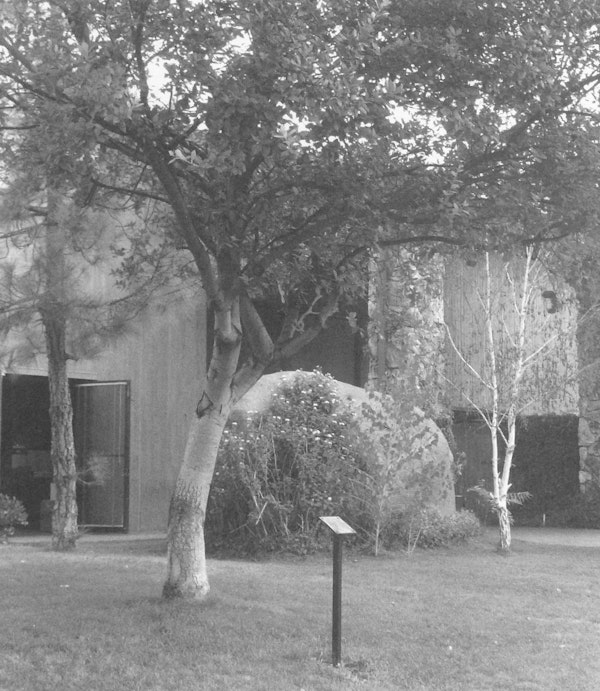

On November 29, 1980, Howard Craig had died of cancer. Craig, who had teamed with Al Buck in the earliest days of the company and had played an enormous role in its growth. An oak tree was planted in his honor. It stood, and still stands, proudly outside the main entrance to the plant. But every time he saw it, Chuck Buck was reminded of the good old days and the people who built the company into the force it had become.

Among those was Don Ham, who retired as the corporation's vice president of sales in

1981. An original director and one of the new firm's first full-time employees, Ham also had played an invaluable role in the development of Buck Knives. During its spectacular period of growth, Ham was in charge of sales, marketing and finance, and his impact was indelible. "Times change and people change, but Howard and Don did as much as anyone to build Buck Knives, and you just don't replace people like that," Chuck Buck noted. "And even though we were doing well, the place just didn't feel the same without them."