CHAPTER 13: NEW LOCKBACKS, NEW POCKET KNIVES

Although the 70s are remembered primarily for the technological strides forward by Buck, the company made two major product line introductions during that decade, with products that remain popular today.

First was the 500 Series of SlimLine lockblade knives, the first spin-offs from the Folding Hunter and the Ranger. These knives embodied the same positive locking action as the 110, but were smaller, lighter and leaner in configuration. And they had a drop-point blade instead of a clip blade. They sold in roughly the same price range.

The Model 501 Esquire (now the Squire) was the first to be introduced. Its drop-point blade is 2-3/4" long, compared with 3-3/4" for the Folding Hunter's clip blade.

Following in short order were the little 505 Knight (only 1-7/8"), the Duke (largest of the SlimLine family with a 3-1/8" blade) and finally the Prince (2-1/2").

The SlimLines have continued to stay on Buck's "best-seller" list, and there now are two choices of handle materials for each of the four models: sleek birchwood, chemically treated to protect the natural woodgrain, or brown bone, called "BuckHorn."

At about the same time the new 500 Series was reaching the market, Buck management was taking a long, hard lock at their pocket knife situation.

Introduction of the 300 Series traditional pocket knives, in the '60s, had received. It was a popular move. But not without out its problems.

Even though the switch to Camillus had been a good step forward, the dilemma of maintaining Buck quality standards remained a matter of deep concern.

So, to ensure quality that met Buck's strict standards, the decision was made to

create and design a new, heavy-duty line of pocket knives that would be manufactured by Buck.

They would be designated the 700 Series, and the plan was to drop the 300 Series as soon as possible after the 700s were established in the marketplace.

The 700 Series, consisting of four models, made its debut in 1979. These new pocket knives were heavier duty, with stainless steel bolsters, liners and rivets, and hollow-ground blades made of 425 modified stainless steel.

Even though they were more expensive, the 700 Series knives proved to be very popular, reaffirming the company's conviction that quality in knives is a key factor to success.

With the experience gained in manufacturing its own pocket knives, coupled with the belief that two levels of pocket knives were important to their dealers and to their customers, it was decided not to drop the 300 Series after all.

Instead, Buck Knives redesigned the four most popular models (the 301, 303, 305 and

309), and started producing them in their own factory in 1987.

The control gained by making these knives in their own facility made it possible to upgrade to the quality level they had been seeking.

Continuing demand for the full 300 Series made the company reluctant to drop the others.

And the remaining eight models are still produced outside; but their volume amounts to only about 20% of the total 300 Series sales.

CHAPTER 14: MORE " ADVENTURES" OF THE '70s

The Company Grew at a fairly steady rate through the "70s, but not without an

occasional faltering step.

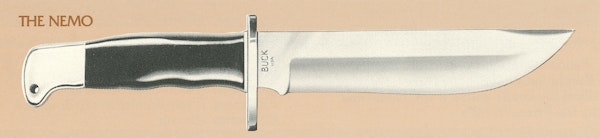

For example, they developed a knife for undersea divers, called the "Nemo." Hoping to tap a wide-open market during a time when skin diving and scuba diving were growing in popularity, Buck spent nearly a year refining a multipurpose knife that would meet the specialized needs of the divers.

The knife worked great, but had one fatal flaw: it rusted in salt water! It was discontinued almost immediately, and today it's highly sought after by collectors.

There were occasional legal problems, as well. Particularly troublesome was the fact that some law enforcement agencies classified the Buck Folding Hunter among the "switch-blades" that had been banned by ordinance in many cities.

"Obviously, in the technical sense, the 110 was not a 'switchblade' knife," Al Buck recalled. "But you could take a screwdriver to it, loosen the tension on the blade, and get it to the point where the blade would open if you snapped it hard enough toward the ground.

"This made it something of a gravity knife,' and many police departments placed gravity knives and switchblades in the same category."

The Buck management team considered this interpretation extremely dangerous because it involved the company's most popular model.

"Our real concern was that this interpretation would actually be made in a courtroom somewhere, and then it would go into the books as a precedent for later litigation," Buck explained.

The turning point came in Solano County, California, where the assistant district

attorney was pursuing an assault case that involved a Buck Folding Hunter.

"When he first contacted us, I think he honestly felt our knives might be illegal," Al Buck said. "But Howard Craig went up there, talked with him, and convinced him that the knife that came from our plant was — in no way, shape or form - a gravity knife.

"However, to show our good faith, we said that we would change the design of our knife to increase the spring tension even more. Not only did that Solano County assistant D.A. absolve us of blame, we used his letter to answer similar questions, whenever and wherever they were raised, even though different local laws might apply."

Despite these obstacles along the way, the Buck company forged ahead. Streamlining of the production process, establishment of new product lines and maturation of a bullish market resulted in amazing growth of 121% between 1973 and 1976.

"A variety of key factors all came together for us in the mid-"70s," Ham noted. "The American economy was strong. Sales were strong. Our production people were doing a great job staying on top of our orders. We went from being a small knife company to a medium-sized knife company almost overnight."